Initially uploaded: 7th February, 2021

Before getting into this, if you are after something more concise, I also wrote this much shorter version on Ødegaard’s profile (albeit without the comparisons to Emile Smith-Rowe), so feel free to read that one if you prefer. Either way: enjoy, and let me know what you think.

Intro

At the end of the January transfer window, Martin Ødegaard became the second Real Madrid player to join Arsenal on loan. The move is the attacking midfielder’s fourth away from the Spanish giants, with his 2019/20 campaign for La Real proving to be a great boost for his reputation.

Unfortunately, his plans to become a staple in Zinédine Zidane’s starting outfit has not quite come to fruition just yet, partly down to the player himself having to continue to barter with his own body in attempt to last for longer minutes on the pitch due to ever-present injury-related problems. With his minutes first team minutes in the first half of this season continuing to falter, it’s no surprise that he’s looked elsewhere for more assured game time.

So, as head coach Mikel Arteta looks to find his Mesut Özil replacement in the form of the Norwegian, here’s a dive into what kind of player the 22-year-old is, and how he stacks up against his teammate and positional rival, Emile Smith-Rowe.

Attacking

Movement in buildup

Ødegaard has featured in slightly different roles at the two clubs he’s featured for since returning to Spain. Under Imanol Alguacil at Real Sociedad, he was predominantly used on the right of the midfield three in a 4-3-3, which pertained to quite rigid and positional play-like mechanisms; under Zidane, he’s been afforded a fair amount of position freedom from a more central starting position as a #10, either as a part of a diamond or in a 4-2-3-1 of sorts.

At La Real, he functioned well within the pretences of their wide triangular patterns. He offered himself up to the ball-holder frequently and satisfied the structural necessities by pushing wide, making small horizontal shifts between the lines, and strategically coming close to the ball-holder – all as ways of manipulating space to enable himself to receive in good positions, as well as deliberately pulling opening lanes into others. The horizontal movements most of all were particularly translatable in transitionary phases, where he would often find positive ways to offer at an angle free of any opposition cover shadows, be it wide or central.

During higher phases of play, it was increasingly clear that he preferred dropping off from the frontline to instead fill deeper positions – like that of the fullback’s, facilitating their push forwards in his absence. His discipline in doing so was hugely positive in sustaining pressure, as he was well onto loose balls and clearances when maintaining the team’s shape resolutely.

His preference to instead drop and receive towards the outside of the opposition’s block has become more and more difficult to accomplish since returning to the Galácticos due to the presences of Luka Modrić and Toni Kroos in deep midfield. Because of their dominance and responsibilities with the ball in and around the centre-backs, the Norwegian is often unable to invade the deeper areas, so is instead limited to constant horizontal shifts between the lines.

Unfortunately, these kinds of movements aren’t perfect by any means, either, as it’s in this more rudimentary #10 spot where he doesn’t assess his surroundings as well as is necessary since there is so much more of the pitch to consider. He’ll often gravitate towards the ball-side without scanning around, meaning that he’ll sometimes find himself occupying a position or a lane that then blocks access into a teammate and leaves a position he previously occupied completely vacant. So, having that control in his movement as well as knowing how to move when being given more freedom is something he still has much to work on.

Where his movement lacks most of all, though, is in his lack of variety vertically. Ødegaard tends to shape himself with his back-to-goal, which, without extra scanning, majorly limits his awareness of the entire space around him. Consequently, he isn’t always aware of when the channel he’s occupying is open for him to run further into, be it for the sake of himself or for the sake of his teammates.

Receiving

His aforementioned starting body shape plays a huge part in how he handles passes played into him, and it directly impacts how positive he is able to be once getting a hold of it. An extended consequence of receiving so ball-facing is that he’s then stepping backwards onto the ball with a very closed body – this persists through many of his first touches.

Although he is capable of killing the ball with either foot to help him turn and face in one motion, he is also regularly guilty of maintaining that closed body shape by touching it back out towards the outside of the opposition’s defensive block. In a set environment and system, like under Alguacil, Ødegaard illustrated many more occasions where he had the confidence to let the ball run across his body, however, in this more recent, less restricted role under Zidane, he’s struggled more so as there natural rotations in place are much more improvisational.

What has been the same throughout, though, is his blind-sightedness of his teammates’ positions when controlling the ball, especially when it’s backwards. As a byproduct of these, he then finds himself playing short into teammates in congested areas, or even running the ball into similar types of tight pockets where there’s no room for escape.

Even more damaging is how long it usually takes him to align himself with the ball and the goal correctly. Big parts of the reasons as to why he struggles under slight amounts of pressure from his blind-side are because, firstly, he doesn’t form a more flexible body shape that could allow him to guard the ball more closely as well as shift his body more coherently, and, secondly, he counts too much on his stronger, left foot to do the work. Therefore, he can sometimes need as many as 2 or 3 additional touches just to turn, face and release the ball.

So, when combining the two, it’s clear to see how these factors would seriously limit not only his ability to link instinctively in tight spaces, but also how capable he is of evading pressure. With Making it anything but a surprise that his most prominent pieces of combination play would stem from when deep areas where he has time to lift his head and spark his own combinations from a standing start.

Ball-carrying

Somewhat touched on in the prior section, it’s the way Ødegaard uses – or, rather, fails to use – his body that impacts his pressure evasion. The 22-year-old is almost anything but a needle player as his consistently tall-standing stance prevents him from spreading himself to be able to, not only change direction, but to get his body quickly across to the directions of opposition challengers. Given his consistent lack of blind-sided awareness, it is then no surprise that he is regularly caught out and unable to fend off challenges with just a moment’s notice from behind.

In many ways, this is similar to how Smith-Rowe is. Even though the current Arsenal prospect has shown more promise with his first touch despite his back-to-goal starting positions, he, too, struggles with getting his body over the ball. The difference here, though, is that the loanee actually has a better burst to him from standing starts.

As his 3.7 dribble attempts per 90 for La Real last season might go some way to suggesting, the attacking midfielder boasts more confidence to instigate ball carries. With his stronger foot on the cut-in, he’s fairly proficient in shifting it to the outside sharply enough to evade short tackle attempts. His dribbling, overall, can be much more forceful than that of Smith-Rowe’s, as the Real Madrid man is willing to attack gaps between opponents and chances to run inwards across the midfield line when the opportunities present themselves.

Especially during weaving runs in from the wing, he has the ability to ride challenges well physically – which is about the only time he’s able to contest an opponent successfully in this manner – as well as the peace of mind to fake his actions to buy time and/or space in front of an area where balls through the lines can be so much more dangerous.

But, since all of the emphasis is on feeding runners, this #10 is far from being an illusive dribbler on the counter. Whereas Smith-Rowe is more than able and willing to take the ball in his stride and at pace, Ødegaard prefers not to engage too heavily in direct duels when possible. And, his alluded-to awareness issues also play a hand in him not being able to carry the ball forwards individually from the get-go.

Passing

The Norwegian has offered up some moments of magic with his passing and has showcased a promising amount of variety but, among other negative factors, he suffers from a lack of precision.

In terms of volume, Ødegaard’s average of 57.5 passes attempted per 90 for La Real makes for good reading, as he clearly has the capacity to be a high volume contributor especially when he’s allowed to come deeper for the ball – unlike Smith-Rowe in both cases.

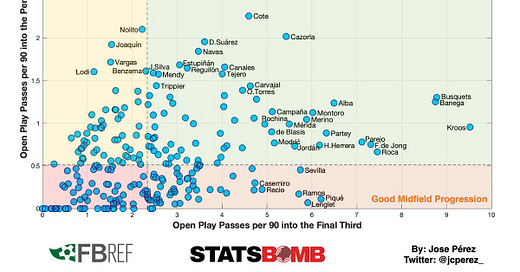

For La Real, he averaged a progressive distance of 245.9 yards via his passes, which is above either of the totals Mesut Özil had offered during his 2018/19 and 2019/20 campaigns, and is significantly higher than Smith-Rowe’s output. As is better illustrated in this fantastic visual from José Pérez below, it’s easy to see how much of an impact he has from deep, and just how penetrative a force he can be when at his very best.

The drawback to these numbers is that his completion rate was at 80.9%, which is a decent figure but not as squeaky clean as you’d hope for from a pass-centric midfielder. This figure seems to be mostly held back by 55.5% long ball (>30yards) success rate, but nevertheless his 9.43 attempts per 90 is well beyond the standards of Smith-Rowe’s 2.68.

Even though his short passing success rate is at 89.9%, he still has his struggles executing simple things like return passes as part of combinations, layoffs for wall passes, and balls into wide players (transitionally or otherwise), which often felt guilty of misplacement and/or weighting issues.

Having an impact on all of this is his lacking operation speed. Tying into the aforementioned issues relative to his controlling of the ball, the attacking midfielder doesn’t get his head up quickly enough to spot and release passes sharply, which is supported by the fact that his slow body angling over the ball means his next action can often be skewed towards the side from which he’s received the ball.

Moreover, he doesn’t boast a great level of awareness in regards to the whole pitch, so when he receives in a tight pocket of space between the lines, he might be able to bounce it off of a close-by teammate but he won’t then have the awareness to know how to act immediately afterwards. Or, more damagingly, he’ll end up being the middle man between the lines and will play to the nearest option whilst completely failing to spot a slightly more distant option who is in a more dangerous position.

This translates through to his bigger passing opportunities, also. There are one too many occasions throughout most games where there is an opportunity for the 22-year-old to feed a run over the top, or deliver a ball into the box, or play a diagonal for a runner, where instead he will proceed to play it safe. Amongst many of the aforementioned factors, this could also be tied to how he keeps his head down when receiving – especially when in a tight pocket – and due to his confidence and willingness, or lack thereof, to attempt them.

The moment of delay, the one extra touch he takes, are small aspects holding him back from acting on dangerous situations in quicker fashion. It’s often also blatantly evident during dangerous counterattacks, which calls into question his decision-making process. His somewhat subdued figure of 2.2 shot assists per 90 under Alguacil’s guidance goes some way to illustrating this.

When he’s aware of multiple runners, his choices aren’t bad, per se, but the type of pass he plays into his chosen runner could do with improving, still. But he can only test this so many times given that his head-down instincts continue to limit his field of vision to maximise attacks and stretch transitions as well as he possibly can.

However, where we see the best of his final balls is from set-pieces. Ødegaard is a fantastic deliverer of the dead balls from all angles and distances. He’s able to vary the placement and the type of his crosses well. Although they also suffer from occasional weighting issues, it’s of little surprise that 43.64% (0.96 per 90) of his shot assists came from dead-ball situations up in the north of Spain.

He has a good understanding of possession tempo via game states that juxtaposes the way Smith-Rowe approaches the game. Whereas Smith-Rowe is all about high-paced instigations at all times, which is great for picking the lock of defensive blocks, Ødegaard appears much more settled in winning game states where he’s better able to assert himself on the ball and steady the tempo of the match.

All in all, his passing side paints a frustrated picture despite certainly eclipsing Smith-Rowe in these regards.

Goal threat

Ødegaard’s 4.13 shot-creating actions (direct involvements in shots, be it through shooting, passing, dribbling, or drawing fouls) per 90 are mostly made up of his creative output, which speaks to how limited he is as a goal threat.

What pegs him back is that lack of urgency and instinct to attack the box. He’s always looking to receive freely at the edge of the box but never with his eye on the spaces inside of the box. Although this sees him exploit gaps deep of the opposition’s back-line, it also results in him failing to exploit channels that have been drawn open by teammates with no-one else left to capitalise on them. In comparison, Smith-Rowe shares similar deficiencies but is still more than capable of identifying a channel to attack across the face of goal, even if he’s often late to get there.

This is also visible in how he moves after releasing the ball. Whereas Smith-Rowe has a different kind of instinct that informs him of how and when to make a great 3rd-man run in general play, Ødegaard doesn’t possess that. He will happily move into a forward pocket once releasing the ball from deep, but he isn’t ready to do this unless it’s a pre-meditated movement stemming from his own action, and even then these tend to happen either side of the midfield line, rather than extending to the space in behind.

His deeper positional tendencies highlight this just as much as his frequent lack of urgency to keep ahead of play during counterattacks. So, it’s unsurprising that his shots average a non-penalty xG (expected goals) total of 0.07 from 1.74 shots per 90. This massively contrasts Smith-Rowe, whose now much smaller average of 0.7 shots per 90 under Arteta is paired with double the xG per shot figure that the Norwegian boasts.

It’s important to note, though, that Smith-Rowe had averaged 2.14 shots per 90 for Huddersfield Town in his 2019/20 loan spell there, which goes some way to indicating the Arsenal coach’s greater emphasis on higher quality efforts instead of more volume-based efforts. So, seeing a dip in Ødegaard’s shot totals might not be too surprising, and nor would a gradual rise in the his non-penalty xG average of 0.11 last season, even in spite of his inferior attacking instincts.

In regards to the player’s technique, he is once again pleasing on the eye with quite a clean strike of the ball at times – illustrating an ability to generate power and a good level of placement – but his efforts still contain their fair share of inconsistencies.

He likes to drill them across goal when he can but these require him to have come quite far across from the right with the ball, and do still often lack the connection necessary to threaten the goal, and can sometimes come at the cost of ignoring better-placed teammates.

His on target percentage of 34.7% bears a resemblance to Smith-Rowe’s 35.7% at Huddersfield, although the latter seemed to have a better consistency in how well he struck the ball towards either corner when playing in the second tier.

The crux of this point is that his 0.14 goals per 90 are an indicator that he should not be relied upon as a goal threat in remotely equal measure to his passing talents, which might yet be a collision point for Arteta in the way he seems to like his attacking midfielders to operate.

Defence

Pressing and counter-pressing

Ødegaard is unquestionably a player quite full of enthusiasm when defending from the front. Under Alguacil, he averaged a very desirable 18.4 pressures per 90 with a success rate of 24.2%. With a quarter of the minutes, Smith-Rowe’s numbers in this regard are also strikingly similar, and they both share a number of similarities in the specifics of how they press onto opponents.

In truth, the new signing is a weaker presser than the mainstay. Whilst the Madrid loanee is aggressive out onto opponents, he’s also inconsiderate of his surroundings. His body shape when stepping out is typically very narrow, like Smith-Rowe’s is quite often, which narrows his cover shadow and, when overcommitting, has a drastic effect on his ability to change directions. So, when he moves too far out in such a way, he can be evaded by simple touches forwards, against the grain.

In the technical sense, the same can be said of Smith-Rowe’s approach in how closed-bodied he can be, but he still manages to do this with a good-to-great level of blind-sided awareness to ensure he curves his runs better, which is something Ødegaard does not currently possess. As a result, he’ll leave the opposition #6 wide open or will pre-emptively position himself too high up in an effort to get out to backwards passes quicker but at the cost of leaving paths open into the space behind him.

Yet again, though, there could be parallels in Ødegaard’s progression should there be any under Arteta, as Smith-Rowe had similar issues defending #6s when with Huddersfield but has since become a very astute and effective guarder of players.

His defensive intensity is at its absolute peak following a turnover of the ball. He shows immense pace and assessment of situations in these states to get across and block off free options, as well as having the continued perseverance to harry opposition ball-carriers, even from one end of the pitch to the other.

A strong positive is that Norwegian’s tackling technique appears to be incredibly clean and effective. When he’s able to come into close contact, and isn’t instead beaten as a result of his aforementioned downsides, he’s rarely pulled up for clumsy challenges since he balances his aggression just as well as he does his technique

Defending in a unit

This season, Ødegaard’s had the luxury of more freedom as part of a front two under Zidane, but he had a little more work to do under Alguacil last season. For the latter, he was sometimes a part of the two, where he was then quite slow to get back and didn’t do a lot of tracking.

Just as inconsistent, and as prominent in his pressing, was his lack of tightness to the opposition’s #6 when holding more zonal-based positions. It would be nice to see him apply a level of directness and intensity in the tracking pf his opponents that his similar to the way he does during counter-pressing situations. Generally, he can be quite slow to get tight when man-marking opposition players. And, similar half-hearted efforts have also been evident in other deeper situations, although the most prominent examples that spring to mind are from his time under a slightly more laissez-faire management style with Zidane.

For La Real, he was also asked to defend in the same position from which he attacked (as a right-sided interior), which further highlighted his awareness-based issues as he frequently found himself positioned too high and detached from his own #6, which was especially the case when ball-watching from the far-side. As a result, there was often a diagonal lane to feed the ball through that opponents had often exploited by occupying the pocket of space behind him.

But, with the enthusiasm of his quotes through the chance he has to make a name for himself here, we could see a similar type of defensive transformation to that of Smith-Rowe, who has taken his opportunity by the scruff of the neck post-Christmas.

Injuries and endurance

One of the main question marks hanging over Ødegaard’s head, like it has done with Smith-Rowe, is how sustainable his fitness levels are.

22 of his first 23 appearances for La Real had actually been full 90-minute performances – only missing a small handful of games, however, the midfielder played noticeably fewer minutes across the final 10 league games of the season. Across those 10, he featured 7 times, and was substituted off before the 80th minute on every occasion.

Those concerns continued to manifest themselves this season as he picked up two, albeit minor, further injuries. In spite of his difficulties to find a spot on the team sheet, he has still failed to manage more than a 70-minute display under Zidane.

As is expertly delved into in this video concerning his injury problems, it was at that time relative to his dip in minutes for La Real that his injury problems were beginning to flare up more damagingly. And, with that likely being the case for some of the continuances in his periods on the sidelines since, it’s something to be precautious of despite the level of intensity he’s able to deliver during shorter-length displays.

Smith-Rowe is, again, similar in the fact he is subject to his own fitness limitations, except his are more specifically endurance-related. He doesn’t have the athleticism to carry out the same levels of intensity across back-to-back 90s, twice a week, like Ødegaard had appeared capable of. But, with the two battling for the same position, rotating one for the other during a frantic late-season schedule could prove fruitful.

Conclusion

So, is Martin Ødegaard the man to fill Mesut Özil’s shoes, possibly in a way that, statistically, it seemed like Norwich City’s Emiliano Buendía could? Well, not quite.

Whilst Özil’s shoes are big and largely unfair ones to fill, his shot-creation numbers, the very rough-edged quality of his passing, and his style that skews him towards being an inferior instigator in game states where his team is chasing goals, which puts him at a stage where he’s not at the necessary level yet. When comparing this to Smith-Rowe, he might not be the live wire the Englishman is but he can nonetheless provide a potentially crucial final ball.

It’ll nonetheless be interesting to see if Arteta aims to mould him into a Smith-Rowe shape, or if he will keep him the same as he is now. Because, although they share many similarities, the new signing poses key differences in his approach to possession.

In the short term, though, which is what this deal is made out for (currently), he is an almost perfect acquisition. Him and Smith-Rowe being able to adequately share the workload in the #10 position will facilitate for more consistency in Arteta’s system selection, which could be key to maintaining and further building on this current run of form and the glimpses of quality that are beginning to possibly reemerge.

~

Thanks for reading. If you’re interested in reading about Emile Smith-Rowe since his resurgence under Arteta, I wrote a two-part (Part 1 & Part 2) piece for Scouted Football‘s Patreon page.

Data included in this piece is via whoscored.com and fbref.com.