It's the little things

Arsenal 2-1 Brentford Analysis

Two impressive wins on the bounce have offered an early response to questions over the club’s dry January given the surprisingly open race for 4th.

Although we’re now more than 2 years into Arteta’s spell, there is still a lot of evolution ongoing when it comes to the system and how things work on the pitch, let alone off it.

Since first writing on this substack about the Newcastle home win from late last November, things have improved in many ways. However, much of it feels that way now due to a shift in perspective on my end.

For the majority of pieces I uploaded around that time, I was consumed by what was lacking that most attacking teams ordinarily do. Yet, after seeing first-hand against us, as well in their respective game against Brentford also, the similarities to City have highlighted my own errors of judgement. The similarities on and off the pitch are worth delving into, even if the results and league position make it seem very detached.

Before I dig into the details behind it, in essence, the lack of usual mechanisms (e.g. halfspace runs to open far-sided spaces for quick and incisive diagonal access) are completely deliberate. The focus is to avoid pre-empting and over-committing with movement off the ball, and to instead be fluid when it comes to creating ‘superiorities’ using the ball as a focal point.

So, after this already-lengthy intro, here’s my breakdown of various scenarios from the performance – looking at its stubbornness, why and how it works, and showcasing the differences between this, previous games and the parallels with City.

Superiorities

What’s important to factor into each attacking move, here, are the different ‘superiorities’ attempting to be achieved.

In Pep Guardiola’s positional play, there are the main three of numerical superiority (having the free man/overload), positional superiority (positioning players in a way that offers an advantage, e.g. occupying space between the lines) and qualitative superiority (exploiting and isolating the individual qualities, e.g. 1v1s, 2v2s, etc.).

In the case of our current approach, the structure (positional superiority) best facilitates safe circulation and a very effective counter-press. So, the numerical superiority is always used at the back.

Against Brentford, there were plenty of instances of the far-sided full-back dropping in when the ball-sided full-back was committed high – creating a pendulum-like motion in rotation. This meant that when the near-sided centre-back was called into action, he had 3 central lanes to aim at against, at best, 2 readily-position strikers.

Further ahead, it’s more about positional and qualitative superiority. However, there are two other types of superiorities that go slightly deeper: dynamic and co-operative.

Dynamic is the most relevant because it refers to “the time and the speed (but not only the physical action) in which a player is able to arrive into a space”. This can refer to dummy runs commonly made through the channels, which we often avoid, but can also refer to 3rd-man runs, give-and-gos, and other movements that are important to dismarking.

Co-operative refers quite simply to the connection between individuals and/or the team. As you’ll see in this piece, Saka and Ødegaard, for example, have continued to build on a co-operative superiority of their own over the past months. Meanwhile, on a larger scale, the team as a whole has established it through its truly tireless work ethic.

Wide combinations in Brentford’s half

Most of the 1st half was spent camped in Brentford’s half, as they congested the edge of their third and we looked to pick the lock in a very intricate-but-guarded manner.

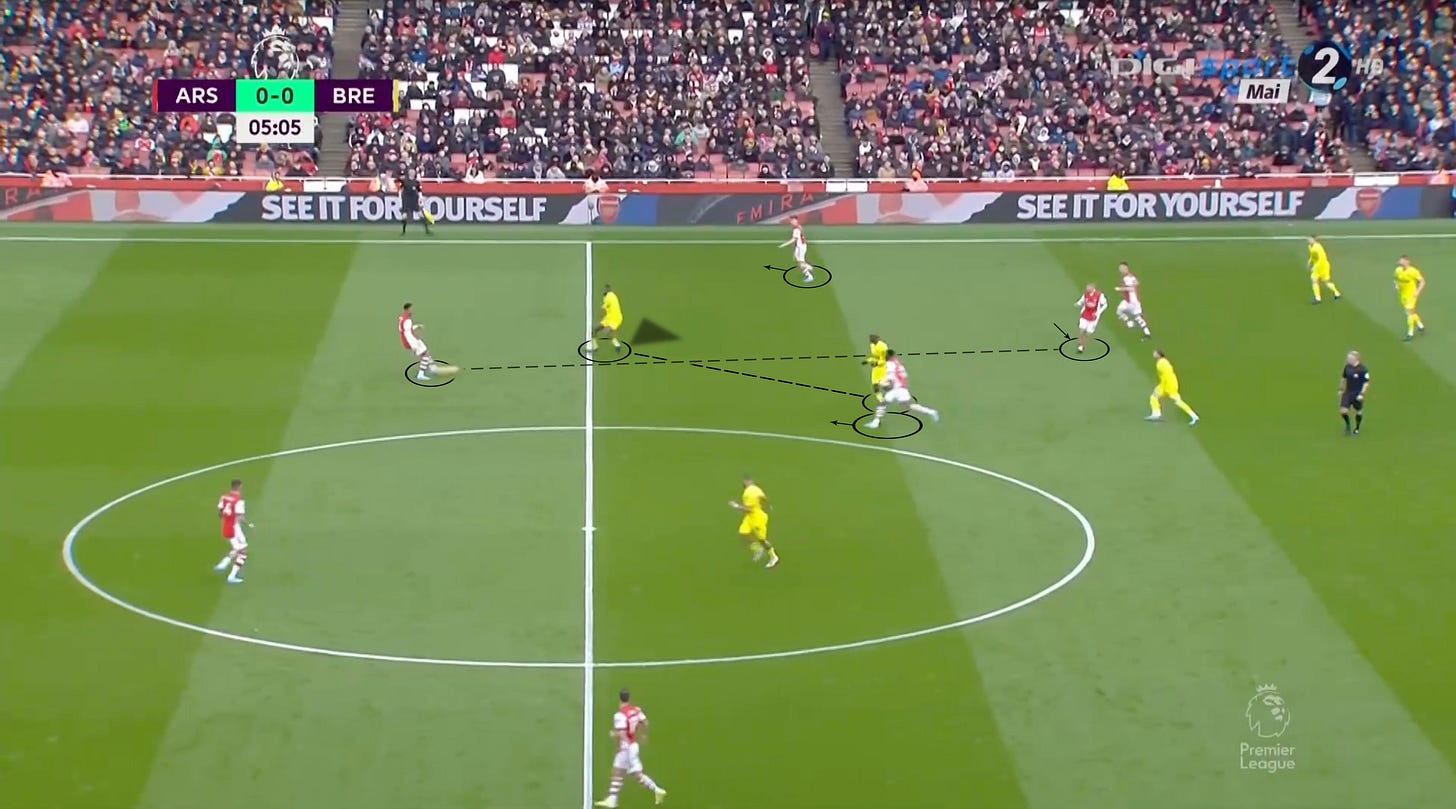

1st sequence

Often sticking to the confines of the 4-3-3 (2-3-2-3 in the more exact sense) structure, the wide exchanges frequently saw each of the respective trios move to the ball in areas on the outskirts of Brentford’s block.

Although one player would usually occupy the inside space to form the triangle, they would tend to act as a player to bounce passes off rather than make runs.

The first receiver would usually be Saka or Ødegaard. In this more transition-like first scenario, though, it’s Saka, as Ødegaard offers outside of the cover shadow with his in-to-out movement.

One of the main details here is how close the Norwegian runs across the wing-back’s blind-side as it distances himself from the wide centre-back, who would have to move uncomfortably far wide to stay tight. For that reason, he has space enough inside to let the ball run across him to be able to face goal-wards.

The next move – the line-splitting move – is the most significant application of the aforementioned superiorities. In this slightly more sheltered role at the edge of Brentford’s block, Ødegaard has more time to view the game and pick his moment.

In general, this is a good approach to maximising his strengths due to his attacking limitations. Whilst that was the case in previous, lesser performances, the speed of his actions when opportunities arose fell into the same lull that the pace of the possession passages did.

In the below example that I wrote about in the Newcastle analysis, Ødegaard is in a similar position and has Saka exploiting an exposed channel nearby, but wasn’t willing to up the pace of his game to find the risky ball through the gap. In the clip, he doesn’t engage his opposite number in the same way, and so the final ball is a much harder one to execute.

Here, though, we see some of those superiorities gelled into one.

First is qualitative: he’s isolated against an out-of-position opponent.

Second is dynamic: because of where the ball has been played, Saka’s run is now firmly on the blind-side of his trackers. In addition to this, he instigated the give-and-go, so has a head-start on his opponent.

Third is co-operative: the timing and execution of reverse ball highlight an improved understanding between Saka and Ødegaard.

To zoom in even further on Ødegaard’s impressive action here, the speed of his two touches (the cut-in and then the release) were frequently able to exploit holes created on the ball side.

They were perfect for allowing him to dial up the pace at a moment’s notice – to act on sudden openings. Cutting against the grain of his opponent, sometimes slightly backwards, can easily force the opposition to shift gears, which heightens the disguise on his passes.

These examples from City at the Emirates are quite alike in their right-sided set-ups, with Bernardo Silva and Riyad Mahrez as inverted attackers trying to exploit the diagonal angle like Ødegaard did.

It’s in many ways clear from that game how much more comfortable Pep’s team, unsurprisingly, are at rotating and overloading the area around the ball. The 2nd sequence illustrating that further in the number of runs made from deep to try and exploit the dynamic superiority it was creating.

In terms of our move, it afforded Saka byline access and a couple of decent options to cut the ball back to. However, movement on the whole (including Cédric’s underlap beforehand) had been more congestive than anything else, so Brentford had an easier time clearing it.

The move doesn’t end there, though, as part of sustaining control relies on an effective counter-press. Simple, defendable crosses like this would be damaging if it left us constantly exposed on the break.

So, thanks to the consistent structure in place, the edge of Brentford’s third is instantly well-guarded. The ball-holder can be immediately pressured, with the main pick-out being smartly shadowed by Cédric for the recovery.

From this point, the move isn’t to catch Brentford out during a moment of disorganisation; it’s to re-steady the ship by resetting safely and repeating the same tricks.

In fact, just to further the comparisons to Arteta’s former boss, Guardiola had/has a “15-pass rule”, in which he believes that his team cannot be properly prepared to cope with transitions or build a well structured attack until they have completed at least 15 passes. Although it might not be quite as literal, the passive pass selection fits in line in the 2nd part of the clip.

In the 2nd attacking phase, Ødegaard, in more regular fashion, gets it to feet up against his opposite number. Continuing that improved level of co-operative superiority with Saka – showing that’s he more confident playing off of him from tighter angles – he creates a dynamic superiority by drawing his opponent across and using the 1-2 to duck into the midfield lane inside.

As I’ll touch on more and more: the delay before the combination sees the pace of the move increase exponentially. This is evident here with the speed of Ødegaard’s next pass into Cédric after Saka’s role helping to pin open the wide space. It’s another instance of him operating at a much better level than before.

Take these comparative examples below from the Brentford and aforementioned Newcastle performances. Ødegaard, as he was during most of the season’s 1st half, was so ponderous on the ball, showcasing slow operation speed. In contrast, the Brentford clips show a player far more willing to take play to his opponent, to engage them, to use this drive to forge openings for shot-creating actions.

Most of our attacks were funnelled down this side as Ødegaard-Saka offered the best solutions to the problems posed in these congested areas. So, similar to how Ødegaard’s cut-in forces Brentford players to adjust their eye-line, the patterns of these recalculations do too.

Below are a couple of examples of this through Partey’s shaping towards the left, only to cut against the grain as we try and exploit the right side further.

2nd sequence

This prior scenario was fairly similar, however, since the left side for this game made for a weaker collective, it wasn’t the ideal side to focus attacks down.

To begin with, it looks even more negative since Tierney, as he has done in previous games, carries the ball very close to a quite static wide teammate. The plan isn’t to go forward just yet – it’s to draw the opposition onto us.

The short exchange is un-pressured until Smith-Rowe returns the pass backwards in a way that can trigger Brentford’s press.

Due to the easy direction, Joshua Dasilva undoubtedly feels that he can use his cover shadow to effectively press all the way up to Gabriel. It’s at that moment when the pace of the move goes from 0 to 100 again.

As Brentford are drawn to look at the deepest point, our near-sided players up the aggression of their movement to exploit whatever fragments of space are opening behind the press. Partey makes a concerted effort to pin Yoane Wissa, thus stretching the channel through their first line of defence as much as possible for Smith-Rowe’s inside shift.

It’s then thanks to the operation speed of Smith-Rowe to bring the dynamic superiority fully into play, as his turn to instigate the 1-2 draws open a space in behind that his own movement can then exploit seamlessly.

Yet another small detail of that combination is the fact you have an attacker not just receiving and turning in space, but one that is there to be the connector. So, Smith-Rowe’s pass quickly ensures that the main receiver between the lines is already goal-facing, which makes the move that much easier to execute in incisive fashion.

Of course, it’s another case of the attacker moving wider to the ball rather than inwards onto it.

When the opportunities are there, Smith-Rowe and Saka have the freedom to exploit their qualitative superiority by taking unexpected steps against the grain to try and beat head for goal more directly, but the priority of safety is still very much at play

This is the case here, also, as the flatness of Smith-Rowe’s position means there’s not much forward room to attack, but his clever shift allows him to step around his opponent.

In most cases, though, the percentage play is resorted to. The initial through ball allows for vertical progression, which is often the main positive, so the pass back isn’t suddenly a fault to the move.

Doing so can help tee up players like Tierney, who are then in space to cross, which is all a further extension of the same backwards-to-forwards motion that we saw at the beginning of this move, and in a smaller dose for Ødegaard’s reverse ball.

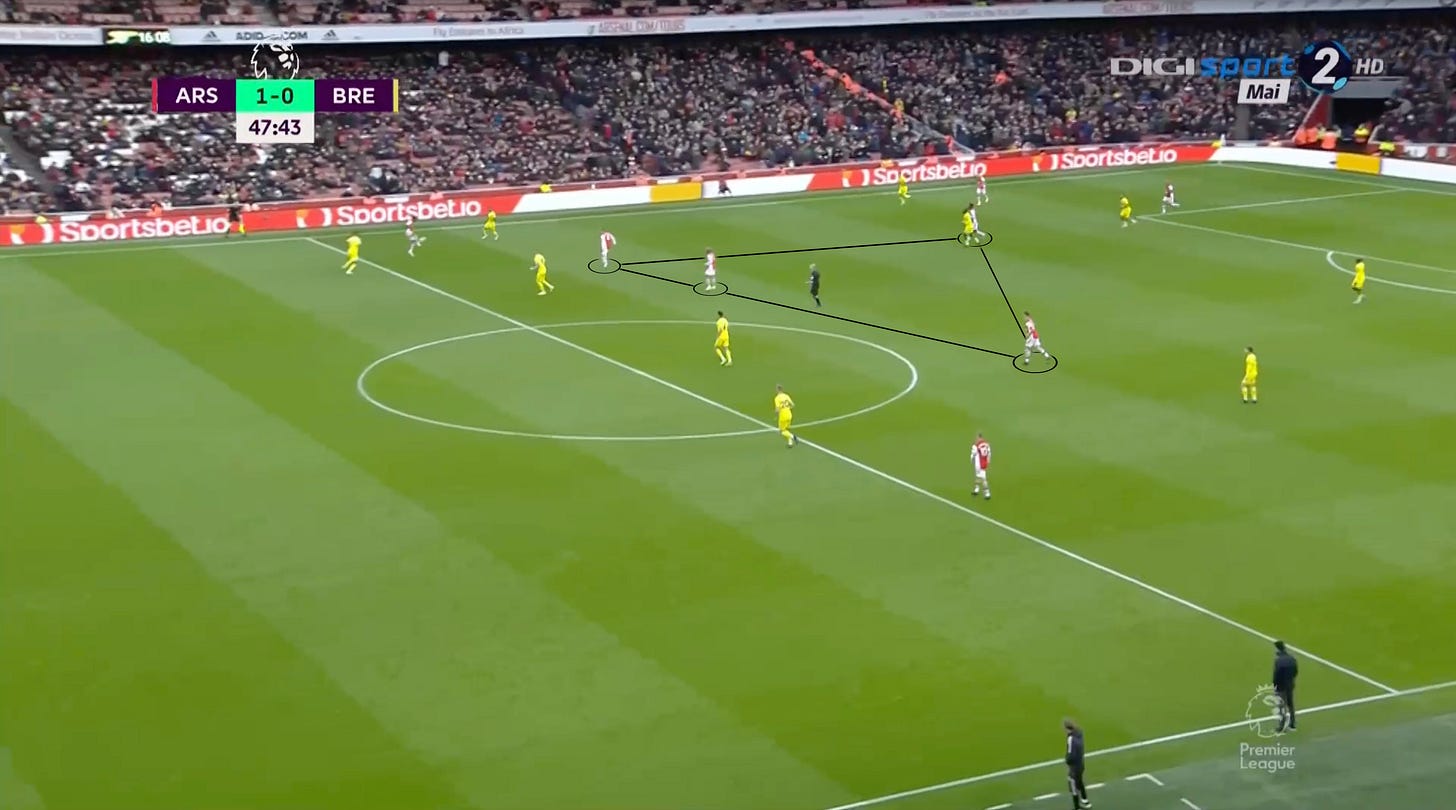

This tends to be the best time for teammates on the far-side to make runs to the face of goal (sometimes from deep), as their runs from deep create a dynamic superiority since, naturally, opponents will find it harder to keep pace with runners going in the opposite direction. Just like this 2nd half example shows.

Then, if or when the cross towards his teammates is cleared, the structure in place allows ours players at the edge of Brentford’s third to smother the receivers.

Stretching the play in the 2nd half

Although we’re are hardly at our sizzling best when breaking down deep blocks – as shown by our 0.75xG racked up in the first half – we absolutely are at our best when playing in transition.

Signs of it were seen in the 1st half from forced Brentford mistakes, but it was even more telling in the 2nd half as the focus shifted.

Our approach changed – looking to exploit the growing fatigue by now stretching the game much more. As such, our total passes in the 2nd half dropped by nearly 100 (from 330 in the 1st half to 232 in the 2nd half), which these pass maps from WhoScored illustrate.

The earliest example of this being the opening goal itself, which demonstrates a picture-perfect example of how well-structured counters have continued to sustain a balance of positional and qualitative superiority, without overstepping the mark.

Lacazette’s disallowed goal

Before digging into the goal, this 1st half example gives an insight into the more common 2-3 shape we use, which is what led to Lacazette’s disallowed goal.

This is where positional superiority comes into play again. Counters of ours will always involve 5 players. Sometimes there are 2 up front, sometimes there are 3, but what achieves superiority is the spacing and staggering.

Here, 3 men to push back Brentford’s defensive line since they already have plenty back, so the best call is to use the space that can be pinned in front. This leaves 2 in the deeper line, in Smith-Rowe and Ødegaard, who fill the halfspaces and stagger themselves well.

Noticeable, though, is how Ødegaard switches gears to move to the outside lane as he already knows Saka will cut-in. So, to maintain the W-shape, his overlap sees him become the wide man on that side whilst distracting those engaged with Saka.

By overlapping, Ødegaard is less likely to take himself out of play with his run, as he can slow down to stay onside, whereas he would have to loop back if he underlapped into an offside position.

The structure then enables a quick and clean transition across, using further patience in this horizontal circulation over an early delivery from Saka to eventually find Lacazette.

Lacazette’s initial wide-of-centre position towards the far side better pins space to help with direct access, and frees him up more when his opponent has to engage with Smith-Rowe here.

Smith-Rowe’s goal

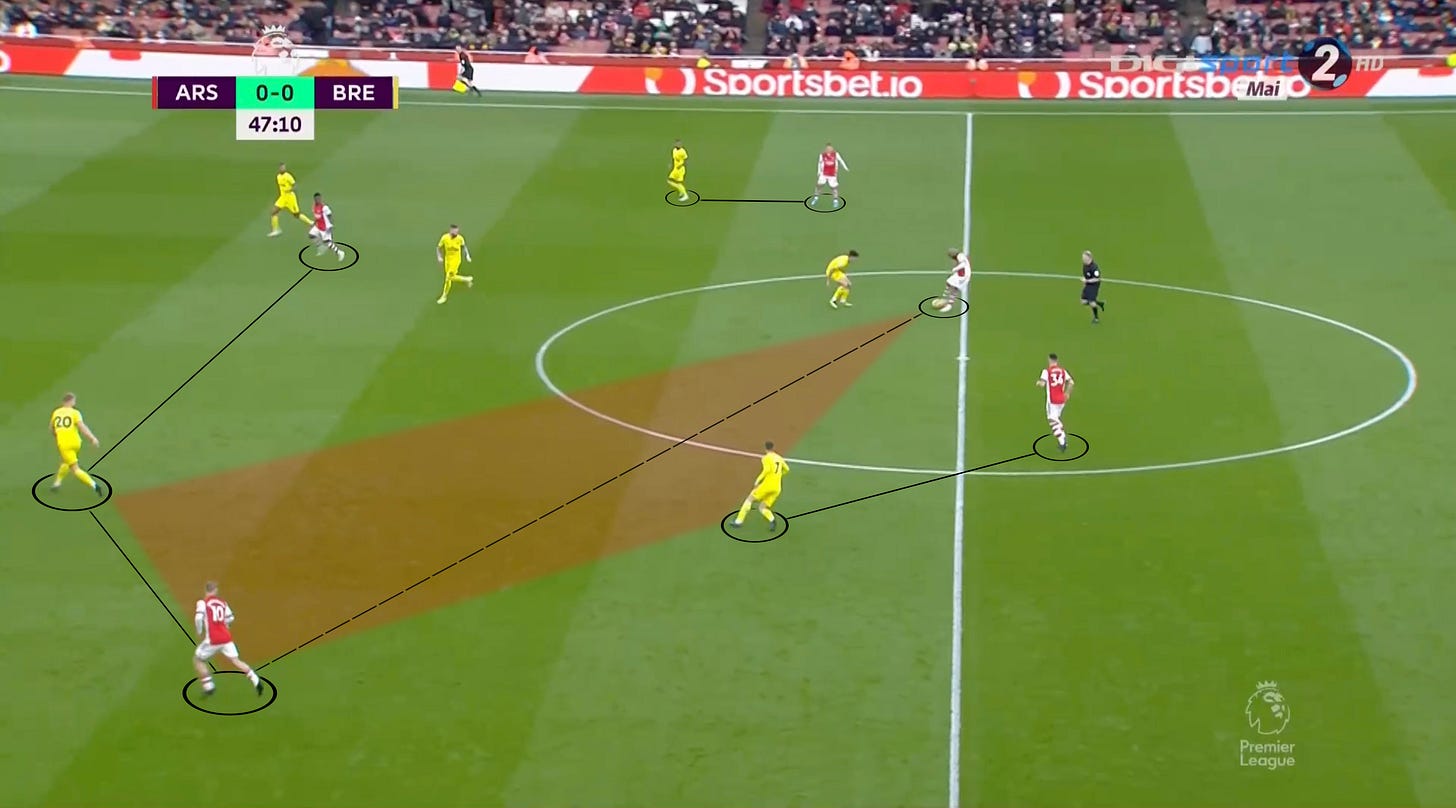

Returning to the 2nd half instance that saw Smith-Rowe break the deadlock, the move is yet another well-structured counter that sustains the same balance, this time in the opposite formation.

The initial shape that led to the unseen pass in this sequence was commonly used in deep buildup phases. Lacazette would drop deep to form a diamond with the two wide men staying high up.

Although there was less focus on using the diamond to play in and then out of pressure in this game compared to previous performances, it’s another parallel with City, who used this shape at the Emirates.

City’s specific use on the day was also a little different, due to the fact that they’re comfortable enough using Ederson out of his box to commit 3 ahead of the diamond instead of just two.

The three central players occupying the positions in front of the visitor’s defence for us allowed for circumstances like below, where the layoff was much easier to win or counter-press. Saka’s pass can afford to be loose because of the coverage.

So, having chosen to build from the back for one of the few times in the match so far, the pitch is now vertically stretched enough that the team can forge their own transition-based scenarios.

This time, the shape is a 3-2, which seems a little negative on the surface but again is all in service of creating margins of error that still allow the best attackers to do the most damage possible.

So, although Ødegaard’s and Xhaka’s flat movements here may seem very prohibitive to the counter, they’re stabilising on the front of forming a rest-defence and are impactful to stretching the space.

This regular view highlights the latter more so, as the 2 sitting either side of Lacazette draw enough attention to keep the space ahead stretched. Meanwhile, Saka’s rotational run into the #9 spot draws the eye of Smith-Rowe’s marker enough.

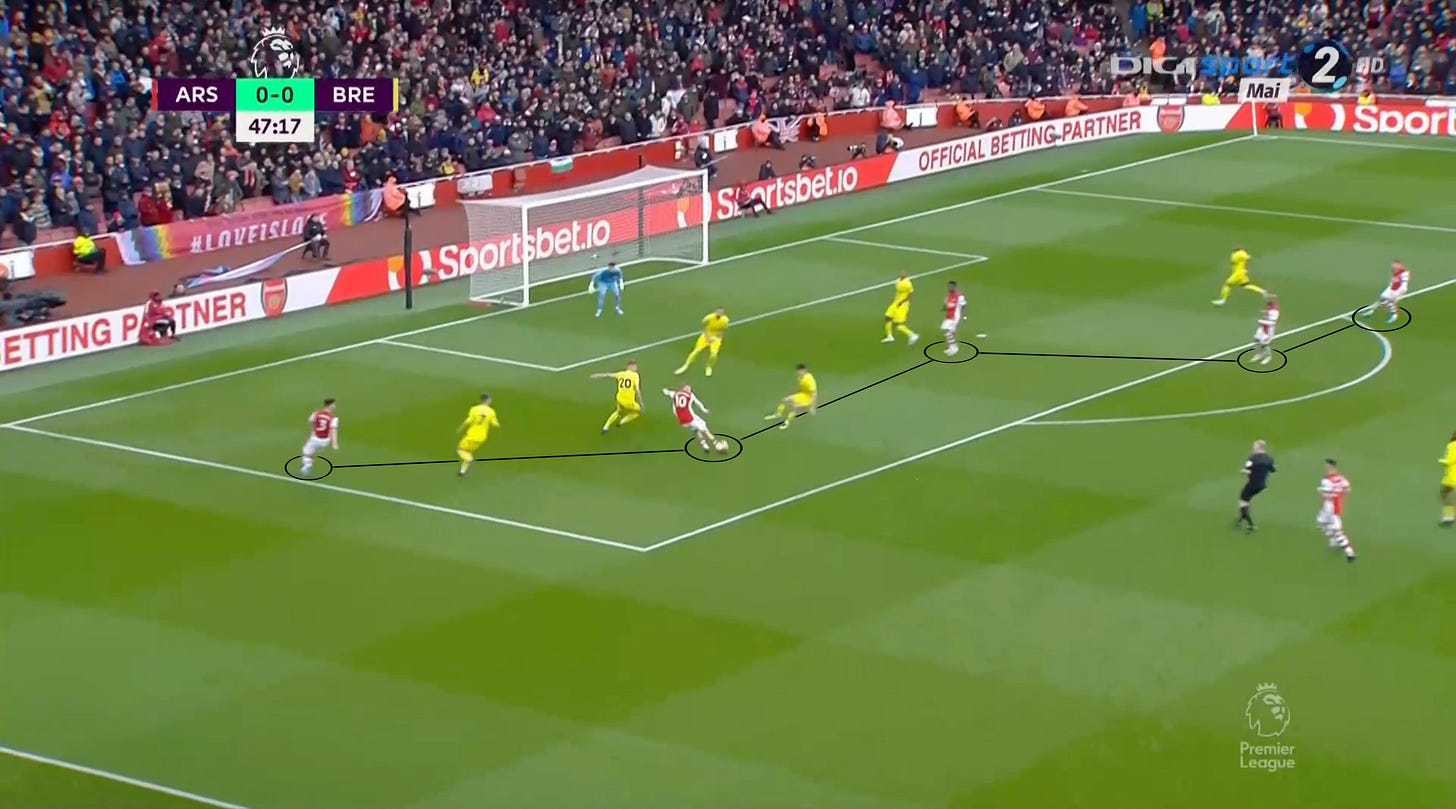

Now in an isolated duel with Kristoffer Ajer, Smith-Rowe can puts his talents to the test as Tierney’s run replaces Xhaka, affording further dynamic superiority (Tierney coming with more pace from deep), and as a result posing questions of the 2 challengers who are now reluctant to prioritise cutting the middle off.

After a superb example of the qualitative superiority demonstrated by Smith-Rowe’s close control and the technique on the finish, the W-shape from before can be seen again.

Playing out of the back

One last sequence that didn’t result in much but felt noteworthy came from playing out of the back and manipulating any signs of fatigue and subsequent disorganisation by the opposition.

Ramsdale had largely been the last port of call and a distributor for the likes of Smith-Rowe when play was set and Arsenal were looking so stretch play in a similar manner early on.

When not doing that, however, he was happy to become more of a reference point, like in this passage out of the back, at a point when he’s now more often called into action.

Initially, Saka is marked up out-of-picture, as is Ødegaard in-picture, leaving just Lacazette. So far, the move isn’t going anywhere.

However, once Cédric carries it far enough to draw Wissa across to him, play is swiftly reset.

2nd time around, there’s a difference in Brentford’s approach. They’re chasing the game now, so they know they need to apply some pressure, but that’s exactly how we’re able to pick them off.

White is happy to slow play down and draw the away side onto him as much as possible, which is the point at which (like in the earlier cited Smith-Rowe move down the left) Partey times his drop (dynamic superiority) to exploit the disorganisation that resetting has caused.

No longer is Saka (who is still ahead, wide, and out-of-picture) being picked up – the wing-back feels responsible for the apparent free man in Cédric, so he pushes up. However, Ødegaard’s circling movement behind his opposite number leaves them neglected enough to also be drawn in by Cédric.

With the pace of play going from 0 to 100 again, Partey finds Ødegaard first-time. This leads to the below situation, where the #8’s over-reliance on his stronger foot is arguably the stopping point for him here.

There’ve been plenty of occasions when these slow buildup passages early in games of the past this season have missed their mark because Partey wasn’t quick enough combining with those offering in pockets between the lines.

Pushing directness and intensity to the edge

Without going into too much detail about it, because there’s only so much to say, the intensity of the team collectively was hugely impressive in the last stretch.

With the trust in the midfield and the attack to work up and down the pitch to close down any opposition transitions and to pressure any clearances, we were a nuisance at every possible opportunity.

This 2nd ball attack above is a very impressive example of such, having recovered possession at the edge of our own box less than 15 seconds prior to Ødegaard snatching up the loose header for the biggest chance of the match.

It highlights the level of the team’s collective co-operative superiority in this regard.

Defending

I’ll be as brief here, too, but there were plenty of positives to take, particularly in the 1st half, but also some negative takeaways in the 2nd half.

On the plus side, there were many clever pressing sequences that felt unique to this game, including occasional pressing traps used to suffocate the visitor’s #6 in buildup.

On the same note, though, Thomas Frank’s side were a little guilty of restricting their own space and not quite capitalising on openings in their buildup passages.

On the downside for us, there were moments of huge vulnerability. There is such an intensity to a lot of the pressing, that work-arounds can leave the back-four very exposed.

Brentford, here, play past the press neatly enough to be able to feed a dangerous channel ball. Were it not for Mbeumo stepping too far across to the ball, he could’ve had a very clean chance through on goal.

This 2nd instance is also quite damning as the recurring use of far-sided halfspace runs managed to cut through the defence to enable immediate box access.

At this point, we had decided to drop our intensity as a block completely – possibly conserving energy for transitions instead.

Thankfully, Gabriel was able to put out most of these fires.

Conclusion

Although it may not be of any news to plenty of others out there who watch City more regularly than myself, being able to identify and come to terms with the parallels has eased certainly eased my mind somewhat.

Whilst I wasn’t able to squeeze in some other instances of creating marginal gains, they help to show the extensiveness of our current patterns. Obviously, we’re not City-level when it comes to rotating and creating superiorities, but there have been clear and obvious improvements over the past few months.

The main question, objectively, rests over its current effectiveness and sustainability. Saka and Smith-Rowe came up trumps again, which was even the case in the aforementioned Newcastle match. They showed their quality for both finishes, but whether that can be enough is the crucial, massive difference between us and Guardiola’s City.

Burnley, among many other matches that came before it, was a fitting example of us not taking the chances that fell our way, which is all the more likely with our squad’s current level.

Even in this match, there were a good handful of attacks blown by mistakes in terms of decision-making and execution. Those were mostly in transition; in general play, the quality-level demands a very high standard to be able to pick the lock early in games and to generate clear-cut chances from them, which we didn’t actually do.

In the short-term, it’s something of a concern because the intensity levels required are so high with quite a thin squad, and it’s not a given that the necessary number of goals will always break our way, and that the ideal flow will be in place to ensure that they do go in.

It makes it clearer to see how this approach is still spearheading the long-term goal of the Champions League over the short-term goal of the Champions League, as it’s hard to see Arteta being dismissed come the end of this season, irrespective of the opportunity at hand. Equally, it makes clearer how upgrades to certain positions can allow for a more fully-formed execution of a Guardiola-like approach that is looking less and less like mimic job.

~

Thanks for reading.

Over on my Twitter you can find even more of this, as well as plenty of my scouting work on individuals. And just as a minute plea of sorts: if you enjoy my work (this or whatever else) and want to help out in any way, I have my CashApp linked to my profile, and I’m also available for hire (DMs open/email on my page, too). I tend to avoid pushing this sort of stuff, but since I put so many hours into my work, I thought I’d make the above possibly a little more known.